Blog

Caution and Opportunity: Understanding the Economic Risks of the AI Revolution

Introduction

Technological innovation is often accompanied by periods of rapid investment and heightened expectations. In financial markets, these episodes can sometimes result in economic bubbles, where asset prices increase much faster than their underlying value, creating wealth that is illusory and foundationally does not exist. Since the launch of ChatGPT, there has been unprecedented investment into artificial intelligence, accounting for nearly all of the GDP growth in the first half of 2025. [1],[2] This incredible economic growth driven by artificial intelligence in a time where dual inflation and unemployment concerns are rampant has prompted discussion about whether the current enthusiasm reflects sustainable progress or risks repeating past patterns of speculative excess.

What Is an Economic Bubble? Why Should We Care?

Economic bubbles develop when asset prices rise far above their true value, driven by speculative investment, widespread excitement about new technologies, and a sense that “this time is different.” [3] The economist Hyman Minsky identified five phases in typical bubbles: displacement due to new innovations, rapid boom, euphoria, profit-taking by early investors, and eventual panic or collapse. [5][6][7] The danger of economic bubbles lies within the speculation or belief in the potential of a technology and its corresponding failure to produce results consistent with that speculation fast enough. [4] After bursting these economic bubbles cause massive financial losses for investors, widespread business closures and layoffs, and broader economic instability.

Historical Parallel: The Dot-Com Bubble

The dot-com bubble of the late 1990s is a classic example of how technological enthusiasm can fuel market excess, and how damaging the collapse can be. From 1995 to 2000, the NASDAQ index soared over 800%, reflecting investor optimism about internet-driven business. By early 2000, many startup companies with little or no revenue had reached multi-billion dollar valuations, and aggregate venture investment in internet firms topped $100 billion.

When the bubble burst began in March 2000:

- The NASDAQ fell by 76%, erasing over $5 trillion in market value by 2002.

- More than half of all publicly traded dot-com companies either went bankrupt or disappeared.

- Roughly 300,000 tech workers lost their jobs in the following two years.

Despite these losses, the frenzy also led to massive investments in telecommunications infrastructure, like fiber optic networks totaling over 80 million miles globally. Though many of these investments were never profitable for their original backers, they dramatically lowered the cost of internet access and paved the way for the digital economy, benefitting society long after the crash.

The Current AI Boom: Bubble or Breakthrough?

Today’s surge in artificial intelligence investment is marked by both optimism and speculation. While AI holds substantial promise for revolutionizing business and productivity, investment in AI infrastructure, startups, and services has reached heights that rival previous technology booms. In June of 2025 alone, $40 billion was invested into data center build out. AI startups raised $192.7 billion in 2025, accounting for a majority of venture capital investment. [8] Leading AI companies account for a significant share of market value, and venture capital activity is increasingly concentrated in this sector. [9]

Valuations for AI startups often reflect immense future potential, with some firms seeing multiples higher than during the dot-com era before even seeing any revenue. Supply chains for critical infrastructure, especially advanced chips and manufacturing capacity, are highly concentrated and vulnerable to disruption centered around bottlenecks like Nvidia and TSMC.

Cracks in the Hype: The Emerging Reality Check

While investment and enthusiasm about AI are surging, actual returns and productivity gains remain limited for most organizations. A recent study by MIT shows that a majority of enterprise AI pilots do not yield measurable improvements and many projects fail to reach scalable production. [10] In many cases, the share of work that can be reliably automated by current AI models is lower than expected, and overall workplace productivity gains have proven slow to materialize. These "J-curve" dynamics mirror the experience of earlier technologies, where large-scale benefits take years or decades to emerge, even after initial hype and rapid adoption.

Technical limitations prevent AI from automating large portions of work without substantial human oversight, suggesting that the promise of agentic AI is, at this point, out of reach. In addition, organizational barriers such as the need to redesign workflows and reskill employees slow down the adoption process. The time horizon for realized benefits in technology is often much longer than investors and markets expect, echoing classic productivity paradoxes from past innovation waves.

The True “Infrastructure Paradox”: What Remains After the Bubble

Even if technological bubbles burst and short-term investments fall short, the capital poured into new infrastructure leaves a lasting foundation for future innovation. For instance, the recent buildout of large-scale data centers has not only expanded physical capacity, but also placed new demands on electric grids, prompting utility companies to innovate for greater flexibility. [11] Concrete demonstrations, such as Oracle’s data center in Arizona, have shown that facilities can actively reduce electricity consumption during peak periods, unlocking substantial grid capacity and making the overall system more resilient. [13] Additionally, the push to supply these energy-hungry centers is accelerating the shift toward sustainable resources. [12] Major tech firms are partnering with utilities to source clean power for data center operations, and this renewable integration is likely to persist regardless of short-term economic outcomes. Thus, even if present speculation proves excessive, the resulting infrastructure can serve as a springboard for future technological and environmental progress.

Policy and Research Imperatives

The growing concentration of economic activity and supply chains within the AI sector introduces novel forms of systemic risk. Recognizing these dangers, policymakers and researchers are increasingly focused on distinguishing speculative excess, managing the fallout from any potential collapse, and finding the right balance between encouraging innovation and promoting financial stability. The IMF and other global institutions have already warned about the risks posed by circular investment structures and fragile supply chains. [14]

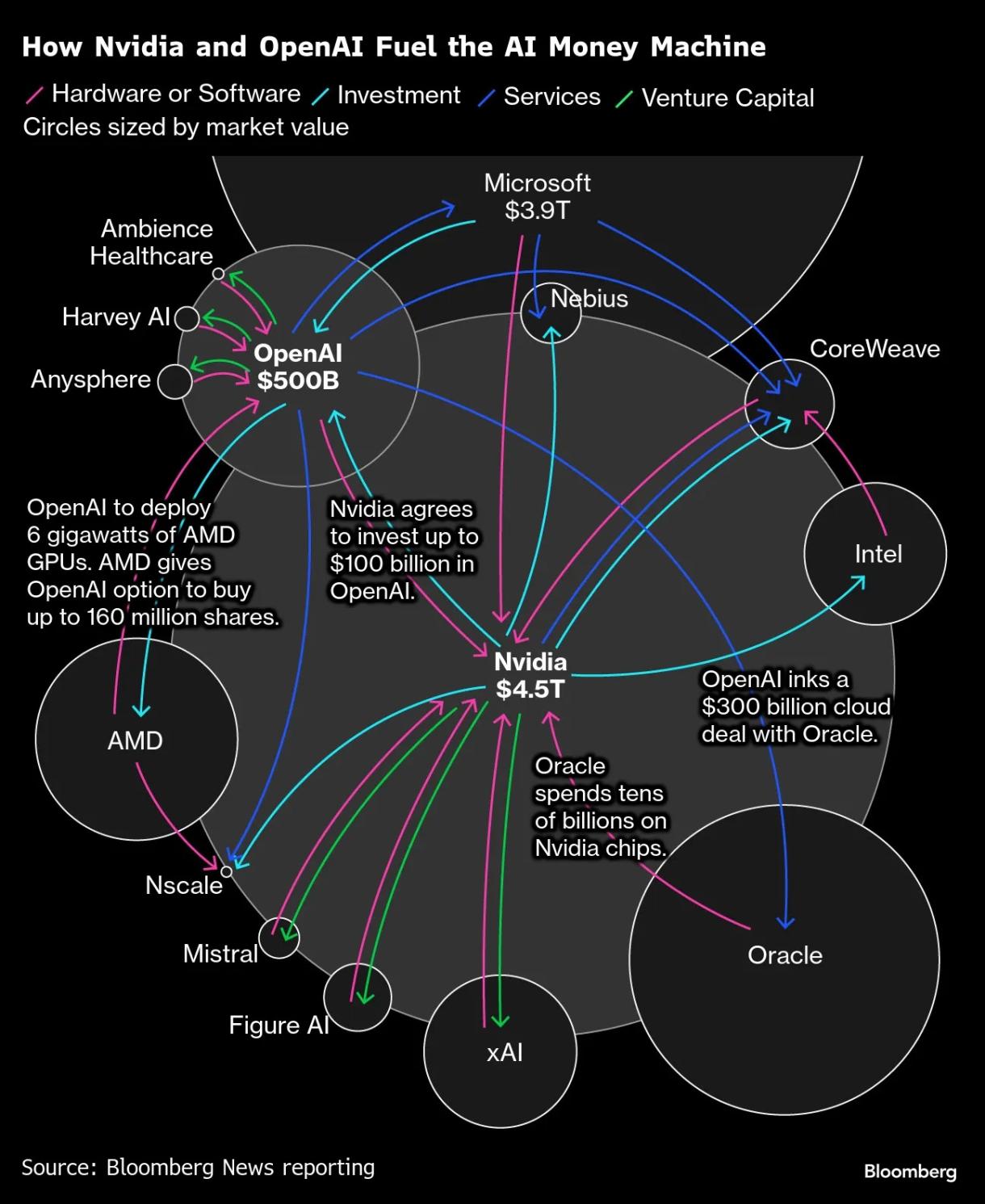

Particularly troubling is the circular nature of investment among leading AI firms such as Nvidia, OpenAI, AMD, Oracle, and CoreWeave. [15] These companies often occupy multiple roles simultaneously, as customers, suppliers, and investors for each other, creating a self-reinforcing loop of capital that can inflate valuations and obscure the sector’s true financial health.

On the supply side, the AI sector’s dependence on hardware from a limited pool of suppliers, most notably Nvidia and TSMC, renders it particularly susceptible to disruptions arising from geopolitical tensions or supply bottlenecks. [17] Compounding this vulnerability, conventional systemic risk assessment tools like credit spreads, expected shortfall, and other standard metrics may offer an incomplete picture for regulators, as intricate financial linkages and overlapping ownership obscure true risk exposures. [16] As a result, policymakers are weighing stricter limitations on bank lending to AI startups in an effort to curb risk accumulation and are considering more robust methods for assessing actual consumer demand. [19] However, given the emerging nature of the conversation around an AI bubble, there is not yet a clear consensus among policymakers regarding the specifics of implementation or what stakeholders would be involved in that process.

Conclusion: Why This Moment Matters

Examining the history and current trends of technology-driven bubbles shows that while the promise is real, the risks are significant. The AI episode stands out for its scale, speed, and the extent of concentration in key infrastructure, but the underlying cycle remains familiar. Careful analysis and proactive policy are needed to guide innovation and to prepare for both the opportunities and challenges that may arise.

Citations

- Furman, J. [@jasonfurman]. (2025, June). [Tweet]. X. https://x.com/jasonfurman/status/1971995367202775284

- Economic Times. (2025, October 8). Harvard economists’ dire warning: Without data centers, US GDP grew only 0.1% in H1 2025. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/us/harvard-economists-dire-warning-without-data-centers-us-gdp-grew-only-0-1-in-h1-2025/articleshow/124396579.cms

- Minsky, H. P. (1992). The financial instability hypothesis (Working Paper No. 74). The Jerome Levy Economics Institute of Bard College. https://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp74.pdf

- Yellen, J. L. (2009, May). A Minsky meltdown: Lessons for central bankers. FRBSF Economic Letter. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. https://www.frbsf.org/research-and-insights/publications/economic-letter/2009/05/minsky-central-bank-asset-price-bubbles/#1

- The Jerome Levy Economics Institute. (2023). Minsky’s contribution to the theory of asset market bubbles. The Levy Institute Blog. https://www.levyinstitute.org/blog/minskys-contribution-to-theory-of-asset-market-bubbles/

- LeBaron, B. (2008). Minsky models of financial instability (Working Paper). Brandeis University. https://people.brandeis.edu/~blebaron/wps/minsky.pdf

- Chen, J. (2023, September). The five stages of a bubble. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/articles/stocks/10/5-steps-of-a-bubble.asp#:~:text=The%20five%20stages%20of%20a,bubble%20grows%20before%20eventually%20bursting

- Holmes, F. (2025, November 3). AI data center building spree hits $40 billion in a single month. U.S. Global Investors. https://www.usfunds.com/resource/ai-data-center-building-spree-hits-40-billion-in-a-single-month/

- TechBuzz. (2025, October). AI startups capture over half of all VC money for first time. https://www.techbuzz.ai/articles/ai-startups-capture-over-half-of-all-vc-money-for-first-time

- Challapally, A., Pease, C., Raskar, R., & Chari, P. (2025, August). The GenAI Divide: State of AI in business 2025. Project NANDA, MIT; Artificial Intelligence News. https://www.artificialintelligence-news.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/ai_report_2025.pdf

- Borgeson, M. (2025, October). Data center efficiency and load flexibility can reduce power grid strain. ACEEE Blog. https://www.aceee.org/blog-post/2025/10/data-center-efficiency-and-load-flexibility-can-reduce-power-grid-strain-and

- BloombergNEF. (2025, October). Power-hungry data centers are driving green energy demand. BNEF Insights. https://about.bnef.com/insights/clean-energy/power-hungry-data-centers-are-driving-green-energy-demand/

- Latitude Media. (2025, October). Catalyst: The mechanics of data center flexibility. https://www.latitudemedia.com/news/catalyst-the-mechanics-of-data-center-flexibility

- Al Jazeera. (2025, October 14). IMF says AI investment bubble could burst, comparable to dot-com bubble. https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2025/10/14/imf-says-ai-investment-bubble-could-burst-comparable-to-dot-com-bubble

- Sorkin, A. R., & Hirsch, L. (2025, October 7). In the circular universe of A.I., OpenAI, Nvidia and AMD. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/10/07/business/dealbook/openai-nvidia-amd-investments-circular.html

- Heyokha Brothers. (2025, October). The circle of financing: Is AI becoming America’s last growth narrative? https://heyokha-brothers.com/the-circle-of-financing-is-ai-becoming-americas-last-growth-narrative/

- Bain & Company. (2024). Prepare for the coming AI chip shortage. Tech Report. https://www.bain.com/insights/prepare-for-the-coming-ai-chip-shortage-tech-report-2024/

- Bloomberg News. (2025, October 7). OpenAI’s Nvidia, AMD deals boost $1 trillion AI boom with circular deals. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2025-10-07/openai-s-nvidia-amd-deals-boost-1-trillion-ai-boom-with-circular-deals

- Eggertsson, G., & Hatgioannides, J. (2025, October). AI bubbles and crashes. CEPR VoxEU. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/ai-bubbles-and-crashes